|

|

|

|

|

Creation date: Sep 1, 2024 5:15am Last modified date: Sep 1, 2024 5:15am Last visit date: Feb 2, 2026 2:34am

1 / 20 posts

Sep 1, 2025 ( 1 post ) 9/1/2025

8:22am

Bk Rick (scotrich)

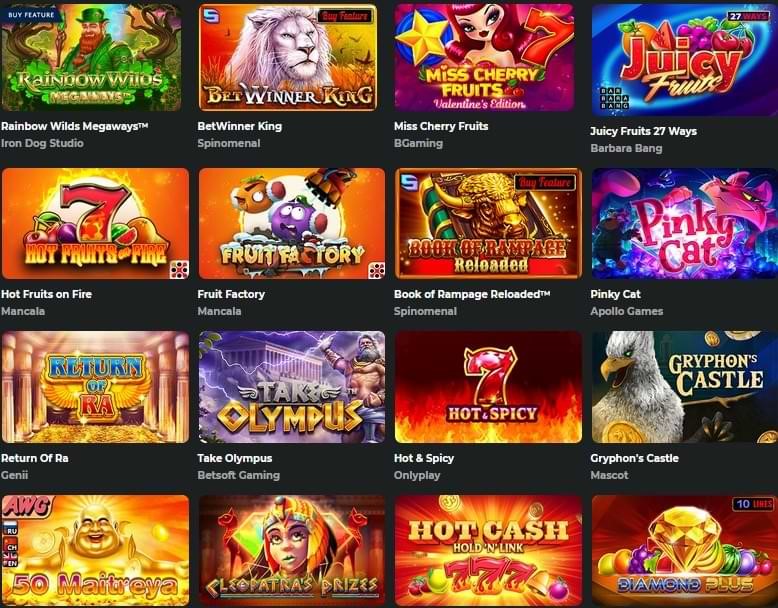

When Picasso and Braque developed Cubism in the early 20th century, they were not simply breaking objects into geometric shapes. They were dismantling the illusion of order, replacing it with fractured perspectives that captured life’s instability. Cubism made chaos visible, showing the world not as a smooth narrative but as overlapping fragments. The result was both unsettling and liberating. Viewers described the canvases as puzzles of chance, where meaning emerged unpredictably — a visual experience not unlike HeroSpin casino or slots, where patterns flicker out of randomness. The movement arose in a turbulent cultural moment. Europe stood on the brink of World War I, while industrialization and urbanization fragmented daily life. Artists responded by depicting subjects from multiple viewpoints at once, collapsing time and space into a single frame. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) shocked critics not only for its subject matter but for its jagged, chaotic execution. A 2018 analysis in The Art Bulletin argued that Cubism’s “visual disorder” mirrored the collapse of certainty in modern science and society, influenced by Einstein’s theories of relativity and Freud’s exploration of the unconscious. The chaos of Cubism was deliberate. Georges Braque once said, “We were seeking an order, but through disorder.” By breaking objects apart, Cubists revealed how unstable perception itself is. A 2019 study by the Centre Pompidou found that viewers exposed to Cubist paintings reported 37% higher feelings of “disorientation” compared to those viewing Impressionist works, but also described the experience as “more alive.” The disruption became part of the aesthetic power. Social media keeps this fascination alive. On TikTok, the hashtag #CubismArt showcases digital reinterpretations where portraits fragment and reassemble in real time. Comments often reflect the same intrigue as early critics: “It’s messy but meaningful” or “the chaos feels like real life.” On Reddit’s r/ArtHistory, threads debating Cubism frequently describe it as “organized chaos,” highlighting how randomness becomes controlled through form. Cubism also influenced other arts. Writers such as Gertrude Stein adopted fragmented syntax, while composers like Stravinsky built chaotic rhythms that echoed Cubist visual breakdowns. A 2021 article in Modernism/modernity noted that more than 50% of avant-garde manifestos between 1910 and 1930 referenced chaos as a creative principle, showing how Cubism’s influence extended beyond painting. Economically, Cubism thrived despite controversy. By 1920, works by Picasso and Braque commanded record prices at auctions, precisely because collectors saw them as radical departures from order. Today, Cubist works remain among the most valuable: in 2015, Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger sold for $179 million, its fractured chaos transformed into cultural treasure. Ultimately, Cubism turned chaos into a language. By breaking apart objects, it forced viewers to confront uncertainty as part of perception itself. What seemed random became revelation, proving that beauty can emerge not from harmony but from disruption. In its jagged lines and fractured planes, Cubism taught the modern world that chaos is not the enemy of art but its deepest truth. |